- Home

- Round Table

- 2024

- Simplified Chinese vs. Traditional Chinese

Simplified Chinese vs. Traditional Chinese

Aug 01, 2024

By: Fang Sheng for the American Translators Association

Simplified Chinese vs. Traditional Chinese, Mandarin vs. Cantonese⏤there are plenty of myths and misconceptions when it comes to the Chinese language. Many such misconceptions even persist in the language services industry, where seasoned language services providers (LSPs) make factual mistakes that they could avoid with a little more knowledge (and asking the right questions). One such misconception: Simplified characters are only used for Mandarin and Traditional characters are only used with Cantonese.

What’s the difference between these Chinese variants, and which one should you choose for your Chinese translations?

Traditional Chinese vs. Simplified Chinese throughout history

Before answering the question, “What should we use⏤Simplified or Traditional; Mandarin or Cantonese?”, we have to go back to some linguistic and historical lessons (without getting too technical).

The Chinese language evolved in such a unique way that there is a disconnect between how it is spoken and how it is written. What you see might not be what you pronounce. In addition, there are dozens of dialects spoken in China, many being mutually unintelligible, as is the case with Mandarin and Cantonese.

The Chinese logographic writing system (i.e., characters) used to be “multi-centered” during ancient times. That is, each state within what is now China during the “Warring States Period” developed its own variant of the writing system, hindering smooth communication across regions. In the Qin Dynasty⏤China’s first imperial dynasty, Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of Qin, instituted a range of reforms aiming at unifying his vast empire, including standardising the writing system. This unified writing system, despite having gone through different eras of war and turmoil, has since been keeping the Chinese nation unified throughout millennia.

In terms of the Simplified vs. Traditional Chinese phenomenon we see today, it is another stage of the evolution of written Chinese and a long history of writing system reforms.

In 1919, when China was humiliated at the Paris Peace Conference, nationalists launched a massive New Culture Movement in an attempt to bring China’s traditional culture into the 20th century. One of the prominent features of the New Culture Movement was baihua, or written vernacular Chinese, an endeavour to break from traditional literary Chinese and bring literacy to the masses.

Some intellectuals, while critically reflecting on the nation’s backwardness, radically blamed the writing system and advocated for Romanisation (as happened in some Asian languages, such as Vietnamese). This, of course, turned out to be futile. With illiteracy rates among the general public above 90% at the time, an alternative proposal was to simplify complex characters, which they thought would make learning to read and write much easier.

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the Nationalist government organised a group of scholars to simplify Chinese writing. However, their work was interrupted by war and political turmoil. Simplification work resumed in Mainland China from 1956 to 1964, when the first General List of Simplified Characters was published. With later minor additions, and a failed second list in the 1970s, the 1964 list has been the basis for standardised Chinese writing in Mainland China through today. In all, there is a total of 2,238 simplified characters on the 1964 list; the rest remain unchanged.

Other Chinese regions⏤Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, as well as the Chinese diaspora⏤didn’t pursue further simplification and continued to use what is now known as Traditional Chinese as their standard writing system.

Differences between spoken and written Chinese

When we talk about Traditional or Simplified Chinese, we are only talking about the writing system. In terms of spoken language, various Chinese dialects are still very much alive and spoken, with Mandarin being promoted as the lingua franca and official language of the People’s Republic of China. While Romanisation did not catch on as a writing system, pinyin (developed in Mainland China) is a modern-day Romanised tool to help transcribe Chinese words and teach Mandarin pronunciation, which is why you probably recognise words like ni hao and xie xie (hello and thank you, respectively).

Mandarin has been used as the official language in both Mainland China and Taiwan. However, for writing, Simplified Chinese is used on the Mainland, while Traditional Chinese is used in Taiwan.

Cantonese, one of dozens of Chinese dialects, is the official language in Hong Kong and Macao. The writing system in Hong Kong and Macao is Traditional Chinese. However, in Guangdong (formerly Canton) Province, where this dialect originated, they use simplified characters as Guangdong is part of Mainland China.

Chinese across the globe

Things are trickier for overseas Chinese communities: in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, the Chinese writing used to be traditional characters. But as China gained influence in the world, the regions’ Chinese communities switched to Simplified Chinese.

For overseas Chinese communities in other parts of the world, including North America, Australia, and Europe, traditional characters used to be dominant. However, with more immigrants coming from Mainland China, the written language has evolved into a mixture of traditional and simplified.

Which version of “Chinese” should you translate into?

For non-Chinese speakers, this complex linguistic landscape can be confusing. If you are wondering which versions of spoken and/or written Chinese you need to translate into, it all comes back to this question: “Who are you trying to communicate with?”

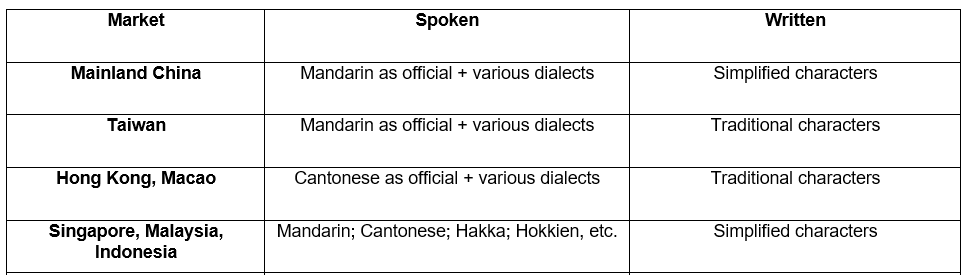

The table below is a summary to help you map your target markets:

If you have content to be translated into Chinese, this chart can help you clarify which script to use. Many professional Chinese translators are proficient in both scripts. However, you still need to practice discretion, as there are regional differences even within the same script or dialectical setting. For example, the traditional characters in Taiwan can be different from those in Hong Kong, as different dialects are spoken. Mandarin on the Mainland is different from the Mandarin in Taiwan, due to differences in terminology and wording preferences.

Archive

2025

- In Case You Missed It;

- Exciting Advancement in Deafblind Interpreting

- Understanding the AUSIT Code of Ethics

September

July

May

April

March

February

January

2024

December

August

July

June

March

January

2023

- Protocols for the Translation of Community Communications

- How much does a translation cost?

- Translators vs. Interpreters